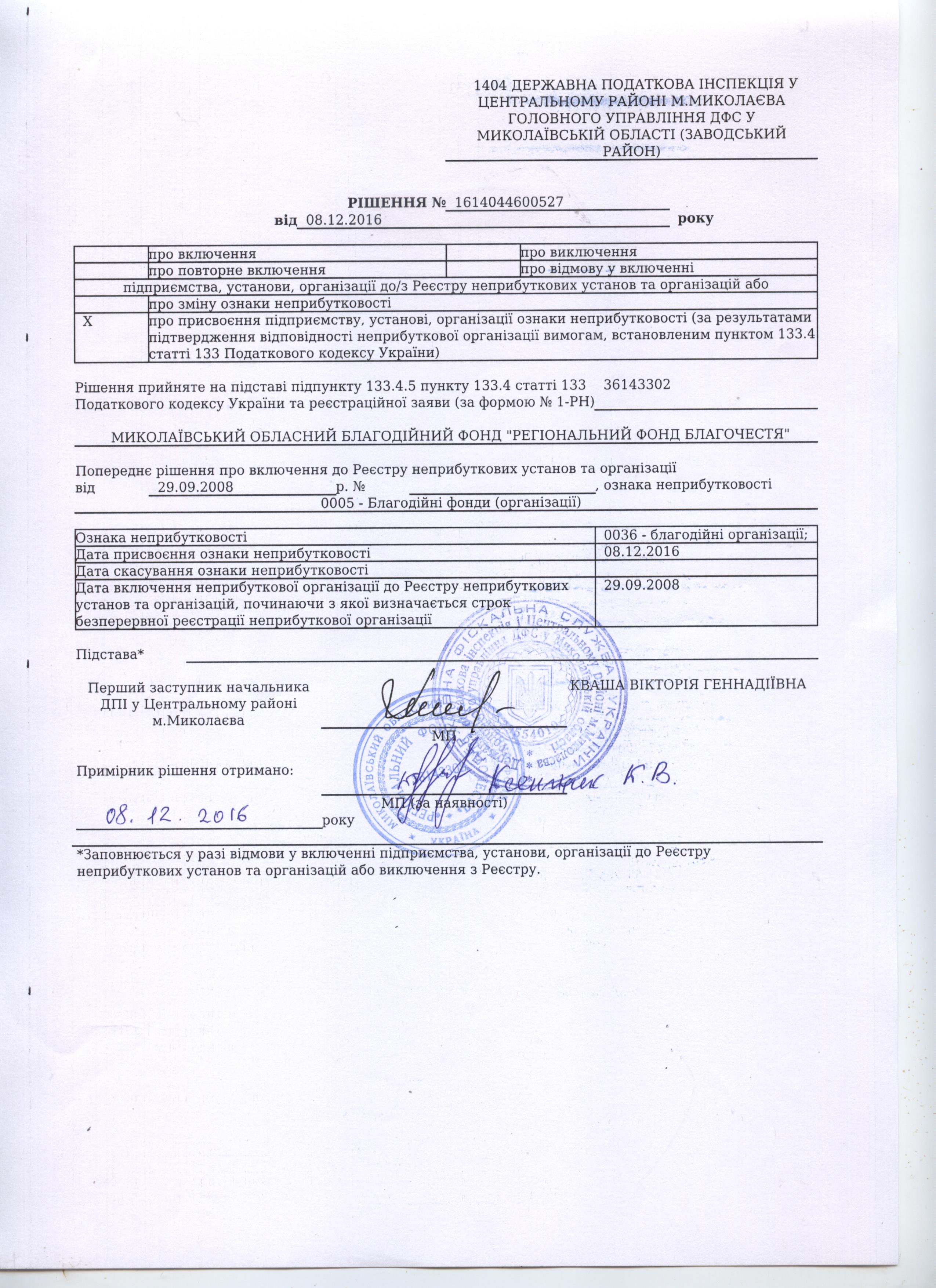

Eight months ago, David Arakhamiya was running a small IT company in the southern Ukrainian city of Mykolayiv. Today, as an adviser to Ukraine’s defense minister, he oversees a massive crowdfunding effort that since March has raised about $300 million from ordinary citizens. The money is being used to equip Ukraine’s army with everything from uniforms, water, and other basic supplies to high-tech gear such as reconnaissance drones.

Yaroslav Markevich, another IT entrepreneur with a small company in Kharkiv, once a Soviet hub for aviation technology, presented a plan to the commander of one Ukrainian battalion to create a drone unit after hearing stories about the efficiency of Russian drones. The commander said yes, and by the time his battalion was deployed early this summer, it was the only one in the army equipped with a fleet of short- and long-range drones. Short-range drones are used to help guard roadblocks—they carry infrared-vision devices that detect approaching enemy soldiers at night—and long-range drones are used to locate artillery targets.

Markevich regularly travels to the front lines to persuade army commanders to use aerial reconnaissance. “We would come to an artillery unit, launch the drones, and show them targets located 20 kilometers away on the screen. It made them ecstatic,” he says. His work with drones raised Markevich’s profile, helping get him elected to Ukraine’s parliament in October.

A crowdfunding effort used to equip Ukraine’s military

A crowdfunding effort used to equip Ukraine’s military

IT experts across Ukraine have been an important part of the volunteer effort to supply the army with equipment. They may enjoy different music than the IT crowd in the U.S.—they listen to underground Soviet bands from the 1980s—but they’re still geeks.

The Ukrainian army had no drones at the start of the war, while the rebels were using sophisticated Russian drone technology. “Back in summer, reconnaissance drones would have saved many, many lives,” says Andriy Horda, a volunteer scout with the Ukrainian army in the war zone. Now, Horda and others say, the troops are equipped with foreign-made drones and homegrown ones built in workshops across the country.

From the minute the army started using drones, the engineers and commanders realized it was cheaper to assemble them locally than to buy them from abroad, Markevich says. Western drones cost upwards of $200,000 apiece; the Ukrainians brought the cost down to about $60,000. About 10 informal groups of technology and aviation experts, all volunteers, are making about 40 drones a month, using open-source software and cameras and other parts bought mostly from China.

“We started cooperating with scientific institutes in Kiev and Kharkiv,” Arakhamiya says. “They helped us a lot with aerodynamics.” The high-altitude drone systems are now comparable to Western versions, he says.

Other military hardware is under development, including encryption devices to protect communications in the field. Early on in the conflict, IT volunteers built a radio communications system that allows frontline commanders to direct the movements of soldiers using a tablet. Arakhamiya says it cost about eight times less than the army would have paid for a system from a commercial supplier.

$60k

Estimated cost of a Ukrainian-assembled reconnaissance drone

Oleksiy Skrypnyk owns Eleks, an IT company that employs a thousand workers in the western city of Lviv, where it produces videoconferencing and event software for hospitals and entertainment companies such as Cirque du Soleil. Skrypnyk is heavily involved in developing new military hardware, including an unmanned armored fighting vehicle that looks like a scruffy version of the battlefield robots in Star Wars Episode II: Attack of the Clones. The Ukrainian army hopes to deploy the vehicle against the rebels.

Despite the burst of local IT activity, Ukraine’s military has a way to go to catch up with Russia’s. “The Russians realized they needed to develop their own drones after the war with Georgia in 2008,” says Yevhen Stepanenko, a Ukrainian military expert and former army officer. Early in the war with the separatists, he led the defense of Mariupol, a port city of half a million in the east that remains under Ukrainian control. He says the Russians “have pretty much every company equipped with fairly sophisticated reconnaissance drones.”

IT is the fastest-growing industry in Ukraine, expanding about 30 percent annually, according to market researcher Roman Sudolsky in Kiev. The industry accounts for $1.5 billion to $2 billion in export revenue a year, mostly from global companies, includingGeneral Electric (GE), IBM (IBM), and Cisco Systems (CSCO), that have outsourced programming tasks to Ukraine. After the war, the country’s IT industry could emerge as one of its most important economic growth engines. Agriculture and steel are Ukraine’s main sources of export revenue; the country was the 10th-largest steel producer in 2013, according to the World Steel Association. Developed in Soviet times, both industries need to modernize. The war makes that harder.

“IT folks have always been independent and cosmopolitan,” says Skrypnyk, who, like Markevich, just won a seat in parliament. “They understand better than anyone what kind of s— our country is in. So now they feel an urge to get out of their comfort zone and change Ukraine.”